|

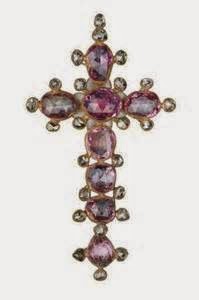

| Pink citrine cross, Cheapside Hoard |

|

| Salamander cabochon brooch, 17th century |

|

| Large stones were frequently bezel set on rings |

The location where the hoard was found is thought to have been the premises of a Jacobean goldsmith, and the hoard is generally considered to have been a jeweller's working stock buried in the cellar during the English Civil War. Cheapside was at the commercial heart of the City of London in the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods, with shops for the sale of luxury goods, including many goldsmiths. The location, a row of houses on the south of Cheapside, to the east of St Paul's Cathedral and to the west of St Mary-le-Bow, was owned by theWorshipful Company of Goldsmiths and was known as Goldsmith's Row, was formerly the center of the manufacture and sale of gold and jewellery in medieval London.

|

| Emerald watch, hollowed out from a Colombian Emerald, 1600 |

Here’s the story:-

June 18 1912. Midsummer in the city, and a normal, dusty, dirty working day for the labourers demolishing three dilapidated tenement buildings on the corner of Cheapside and Friday Street, in the heart of the City of London.

However, at some time that day the routine drudgery took an unexpected turn: the navvies literally struck gold. As workmen began to break up the brick-lined Tudor cellar with their picks, they noticed something glinting in the soil. Furiously casting aside the old brick, a tangled heap of jewellery, gems and precious stones came tumbling forth. What they had stumbled upon was the discovery of a lifetime. Some six feet below the brickwork, in a dank cellar, they unearthed a stash of tangled treasure including gold, jewels, rock-crystal dishes, carved gem figures, cameos, enamelled chains, clasps, bodkins, badges, buttons, beads, an exquisite perfume bottle and an emerald watch. They could not know it at the time, but this was the stock-in-trade of a 17th-century jeweller and had been lying undisturbed for 300 years. The circumstances under which it was buried are still unknown.

The Cheapside Hoard, as it is now known, was – and is – the largest and most important treasure of its kind ever to be found, a captivating collection of Elizabethan and Jacobean jewellery, and a true time capsule.

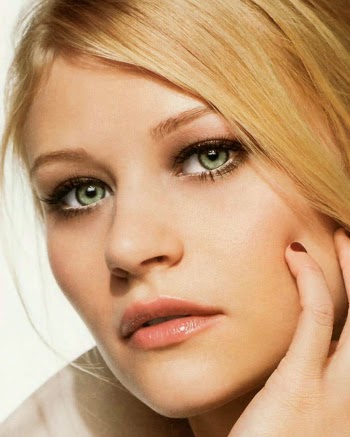

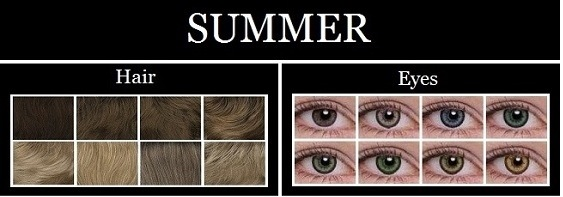

Since it was unearthed over 100 years ago, the Cheapside Hoard has attracted worldwide attention. The Hoard includes delicate finger rings, glittering necklaces, Byzantine cameos and a beautiful jewelled scent bottle. The range of gems is staggering, and demonstrates the international trade in luzury goods in the period – diamonds and rubies from India, pearls from the Middle East and sapphires from Sri Lanka as well as a unique Colombian emerald watch and a remarkable emerald-studded salamander brooch which combines cabochon emeralds from Columbia with table-cut diamonds from India and European enamelling.

Goldsmith's Row was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. The buildings were reconstructed by the Goldsmiths' Company in 1667, and were redeveloped in 1912.

Sources: Wikipedia.com

Sources: Wikipedia.com